Online first

Current issue

Archive

Special Issues

About the Journal

Publication Ethics

Anti-Plagiarism system

Instructions for Authors

Instructions for Reviewers

Editorial Board

Editorial Office

Contact

Reviewers

All Reviewers

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

General Data Protection Regulation (RODO)

RESEARCH PAPER

Depression, traumatic cognition, and death anxiety in pre-hospital and emergency staff depending on prior COVID-19 infection – a Turkish example

1

Disaster Medicine, Ege Universty, Bornova, Turkey

These authors had equal contribution to this work

Ann Agric Environ Med. 2025;32(4):511-517

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objective:

Pre-hospital emergency health staff (PHEHS) and emergency service staff (ESS) who were directly involved in the fight against COVID-19, have been the most affected group among health service units. The aim of the study is to evaluate the traumatic cognition, depression and death anxiety according to having had the COVID-19 disease.

Material and methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted between 15 December 2021–1 April 2022 in Gümüşhane, Turkey, with the participation of PHEHS and ESS (N=304. The Post-Traumatic Cognition Scale (PTCI), Beck Depression Scale (BDI) and Turkish Death Anxiety Inventory (TDAI) were used.

Results:

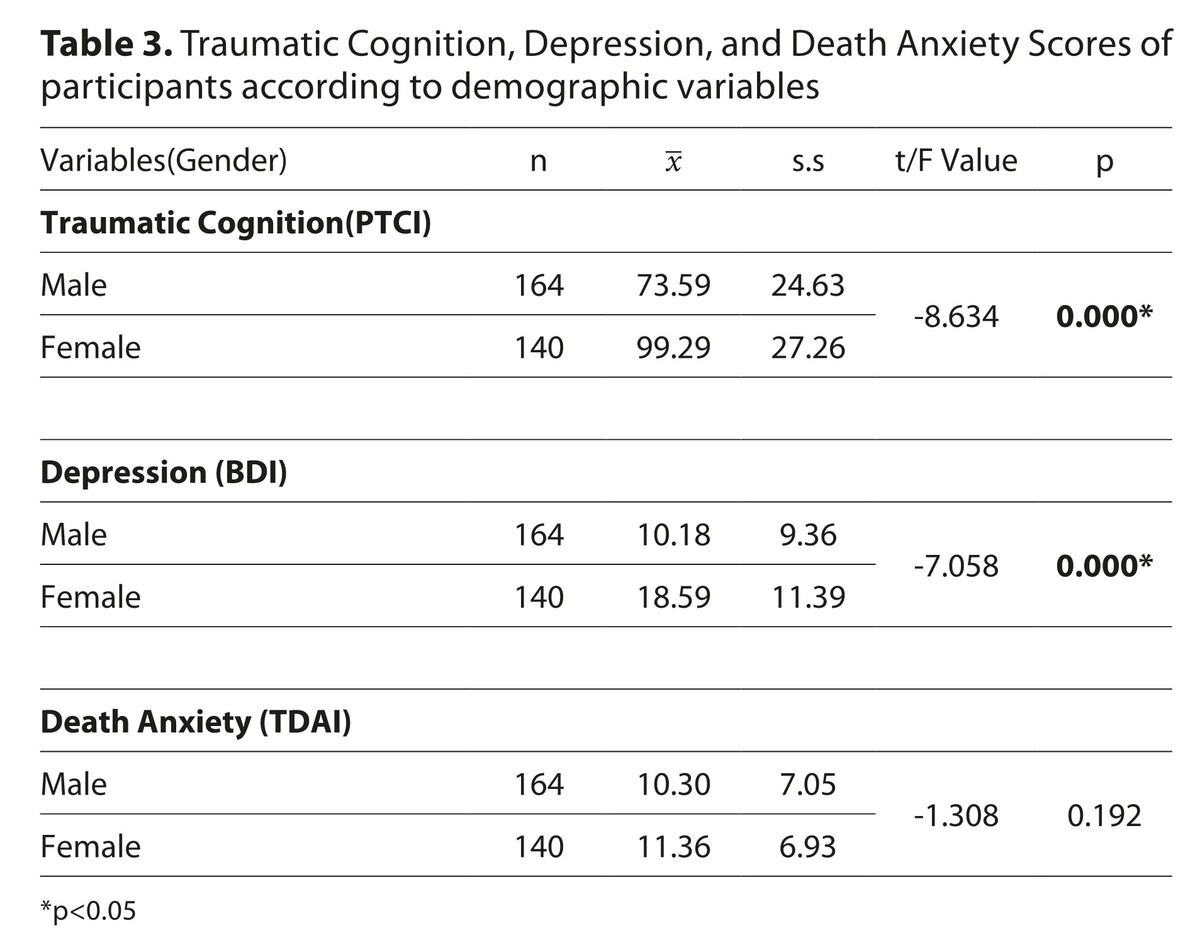

Based on the scoring ranges of the instruments used, the study found that participants exhibited moderate levels of depression (BDI scores between 17–29), high levels of death anxiety (TDAI scores approaching the upper limit of 80), and elevated trauma-related cognitions (PTCI scores within the higher range of 36–252, indicating increased negative cognitions related to the traumatic event). The mean scores of the PTCI and BDI were significantly higher among employees diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to those who were not (p < 0.05). Conversely, the mean scores of the TDAI were significantly higher among participants who had not been diagnosed with COVID-19 (p < 0.05). A gender-based analysis revealed that female participants scored significantly higher on the PTCI than male participants (t = –8.634, p < 0.05). Furthermore, a strong positive correlation was observed between BDI and PTCI scores (r = 0.822), indicating that increased depressive symptoms were associated with intensified trauma-related cognitions.

Conclusions:

Participants had moderate depression, moderate traumatic findings and moderate death anxiety; whereas participants diagnosed with COVID-19 had higher average of trauma and depression findings, lower death anxiety. It is important to take psycho-social measures for PHEHS and ESS providing health services, to take special precautions especially for women and employees diagnosed with COVID-19 who are more affected by the process, to supply and inspect equipment such as personal protective equipment.

Pre-hospital emergency health staff (PHEHS) and emergency service staff (ESS) who were directly involved in the fight against COVID-19, have been the most affected group among health service units. The aim of the study is to evaluate the traumatic cognition, depression and death anxiety according to having had the COVID-19 disease.

Material and methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted between 15 December 2021–1 April 2022 in Gümüşhane, Turkey, with the participation of PHEHS and ESS (N=304. The Post-Traumatic Cognition Scale (PTCI), Beck Depression Scale (BDI) and Turkish Death Anxiety Inventory (TDAI) were used.

Results:

Based on the scoring ranges of the instruments used, the study found that participants exhibited moderate levels of depression (BDI scores between 17–29), high levels of death anxiety (TDAI scores approaching the upper limit of 80), and elevated trauma-related cognitions (PTCI scores within the higher range of 36–252, indicating increased negative cognitions related to the traumatic event). The mean scores of the PTCI and BDI were significantly higher among employees diagnosed with COVID-19 compared to those who were not (p < 0.05). Conversely, the mean scores of the TDAI were significantly higher among participants who had not been diagnosed with COVID-19 (p < 0.05). A gender-based analysis revealed that female participants scored significantly higher on the PTCI than male participants (t = –8.634, p < 0.05). Furthermore, a strong positive correlation was observed between BDI and PTCI scores (r = 0.822), indicating that increased depressive symptoms were associated with intensified trauma-related cognitions.

Conclusions:

Participants had moderate depression, moderate traumatic findings and moderate death anxiety; whereas participants diagnosed with COVID-19 had higher average of trauma and depression findings, lower death anxiety. It is important to take psycho-social measures for PHEHS and ESS providing health services, to take special precautions especially for women and employees diagnosed with COVID-19 who are more affected by the process, to supply and inspect equipment such as personal protective equipment.

ABBREVIATIONS

COVID-19 – Coronavirus Disease

PHEHS – Pre-hospital emergency health staff

ESS – Emergency Services Staff

EMT – Emergency Medical Technician

PTCI – Post-Traumatic Cognition Inventory

BDI – Beck Depression Inventory

TDAI – Turkish Death Anxiety Inventory

SPSS-24 – Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to Leyla Tuncel, Merve

Nas, Arzu Ataman for their assistance in collecting the data

for the study.

FUNDING

Open Access funding enabled and organized by

Project DEAL.

REFERENCES (41)

1.

Zhong R. The coronavirus exposes education’s digital divide. The New York Times. 2020 Mar 17 [cited 2020 Jun 21]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/0....

2.

Ministry of Health Turkey. What is COVID-19? [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 23]. Available from: https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/.

3.

Huremović D, editor. Psychiatry of pandemics: a mental health response to infection outbreak. Cham: Springer; 2019. https://doi:10.1007/978-3-030-....

4.

Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e15-e16. https://doi:10.1016/S2215-0366....

5.

Aljohar BA, Kilani MA, Al Bujayr AA, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 mortality among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide study. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(9):1020–1024. https://doi:10.1016/j.jiph.202....

6.

Chutiyami M, Bello UM, Salihu D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic-related mortality, infection, symptoms, complications, comorbidities, and other aspects of physical health among healthcare workers globally: An umbrella review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;129:104211. https://doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu....

7.

Turkish Medical Association. The second year of the pandemic: evaluation report (2022) [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 23]. Available from: http://www.ttb.org.tr.

8.

Almeida M, Shrestha AD, Stojanac D, Miller LJ. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(6):741–748. https://doi:10.1007/s00737-020....

9.

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. Published 2020 Mar 2. https://doi:10.1001/jamanetwor....

10.

Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD,et al. Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19.2020;38(3):192–195. https://doi:10.3760/cma.j.cn12....

11.

Ruiz MA, Gibson CM. Emotional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on U.S. health care workers: a gathering storm. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S153-S155. https://doi:10.1037/tra0000851.

12.

Hadian M, Jabbari A, Abdollahi M, et al. Explore pre-hospital emergency challenges in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: a quality content analysis in the Iranian context. Front Public Health. 2022;10:864019. https://doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022....

13.

Serrano-Ripoll MJ, Meneses-Echavez JF, Ricci-Cabello I, et al. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:347–357. https://doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020....

14.

Akgun T, Sivrikaya SK. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the pre-hospital emergency health worker. Prehospital Journal JPH. 2021;6(2):31–33.

15.

Foa EB, Ehlers A, Clark DM, et al. The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1999;11(3):303–314.

16.

Yagci Yetkiner D. Turkish adaptation of Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory and validity and reliability study on university students [Master’s thesis]. Kocaeli University, Institute of Health Sciences; 2010. Available from: https://tez.yok.gov.tr/UlusalT....

17.

Beck AT. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. https://doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1....

18.

Hisli N. A study on the validity of Beck Depression Inventory. J Psychol. 1988;6:118–122.

19.

Sarıkaya Y, Baloğlu M. The development and psychometric properties of the Turkish death anxiety scale (TDAS). Death Stud. 2016;40(7):419–431. https://doi:10.1080/07481187.2....

20.

Matsuo T, Kobayashi D, Taki F, et al. Prevalence of Health Care Worker Burnout During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2017271. Published 2020 Aug 3. https://doi:10.1001/jamanetwor....

21.

Moreno Mendoza LS, Trujillo-Güiza M, et al. Health, psychosocial and cognitive factors associated with anxiety symptoms. Curr Psychol. 2024;43:22376–22388. https://doi:10.1007/s12144-024....

22.

Dehbozorgi M, Maghsoudi MR, Mohammadi I, et al. Incidence of anxiety after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2024;24(1):293. Published 2024 Aug 22. https://doi:10.1186/s12883-024....

23.

Kanstrup M, Singh L, Leehr EJ, et al. A guided single session intervention to reduce intrusive memories of work-related trauma: a randomised controlled trial with healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med. 2024;22:403. https://doi:10.1186/s12916-024....

24.

Rizzi D, Monaci M, Gambini G, et al. A longitudinal RCT on the effectiveness of a psychological intervention for hospital healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2024. https://doi:10.1007/s10880-023....

25.

Dosil M, Ozamiz-Etxebarria N, Redondo I, et al. Psychological symptoms in health professionals in Spain after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020;11:606121. https://doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020....

26.

Robertson E, Hershenfield K, Grace SL, Stewart DE. The psychosocial effects of being quarantined following exposure to SARS: a qualitative study of Toronto health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(6):403–407. https://doi:10.1177/0706743704....

27.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. https://doi:10.1016/S0140-6736....

28.

Enlı Tuncay F, Koyuncu E, Ozel S. A review of protective and risk factors affecting psychosocial health of healthcare workers in pandemics. J Ankara Med. 2020;20(2):488–504. https://doi:10.5505/amj.2020.0....

29.

Morgan R, Tan HL, Oveisi N, et al. Women healthcare workers’ experiences during COVID-19 and other crises: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2022;4:100066. https://doi:10.1016/j.ijnsa.20....

30.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:40–48. https://doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020....

31.

Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho AR, et al. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;87:123–127. https://doi:10.1016/j.comppsyc....

32.

Sıraz MF, Değirmenci A, Bozdas MS. The relationship of individual’s emotional self-authority and positive religious attitudes and death anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic process. J Mersin Univer Soc Scien Inst. 2020;4(1):77–88.

33.

Doğan M, Karaca F. A research on the relationship between death anxiety and religious coping in healthcare workers actively working during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Theological Stud . 2021;(55):327–351.

34.

Straker N. Vicissitudes of death anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2021;49(3):384–387. https://doi:10.1521/pdps.2021.....

35.

Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T, Solomon S. The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: a terror management theory. In: Baumeister RF, editor. Public Self and Private Self. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. p. 189–212.

36.

Kilpatrick M, Hutchinson A, Manias E, Bouchoucha SL. Applying terror management theory as a framework to understand the impact of heightened mortality salience on children, adolescents, and their parents: a systematic review. Death Stud. 2023;47(7):814–826. https://doi:10.1080/07481187.2....

37.

Iverach L, Menzies RG, Menzies RE. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(7):580–593. https://doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2014....

38.

Leary MR. The curse of the self: Self-awareness, egotism, and the quality of human life. Oxford University Press; 2004. https://doi:10.1093/acprof:oso....

39.

Tepe M, Indian S, Özoran Y. Determination of death anxiety in physicians and nurses working in internal clinics. J Hacettepe Univer Nurs Faculty. 2020;7(3):262–270.

40.

Akcay S, Kurt Magrebi T. Investigation of death anxiety and death levels in the elderly in the nursing home. J Elec J Soc Sci. 2020;19:2100–2118. https://doi:10.17755/esosder.6....

41.

Neimeyer RA, editor. Death anxiety handbook: research, instrumentation, and application. 1st ed. New York: Taylor & Francis; 1994. https://doi:10.4324/9781315800....

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.