Online first

Current issue

Archive

Special Issues

About the Journal

Publication Ethics

Anti-Plagiarism system

Instructions for Authors

Instructions for Reviewers

Editorial Board

Editorial Office

Contact

Reviewers

All Reviewers

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

General Data Protection Regulation (RODO)

RESEARCH PAPER

Association between cyberchondria and the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) – a cross-sectional study

1

Medical University, Lublin, Poland

2

Institute of Rural Health, Lublin, Poland

Ann Agric Environ Med. 2024;31(1):87-93

KEYWORDS

TOPICS

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objective:

Cyberchondria has been described relatively recently as a behaviour characterized by excessive Internet searching for medical information related to increasing levels of health anxiety. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to a broad set of health care practices that are not part of a country’s traditional or conventional medicine, and are not fully integrated into the dominant health care system The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationship between cyberchondria and the use of complementary and alternative medicine.

Material and methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted from 25 April – 25 December 2022. A computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) survey technique was used. The study population consisted of 626 respondents who took part in the study.

Results:

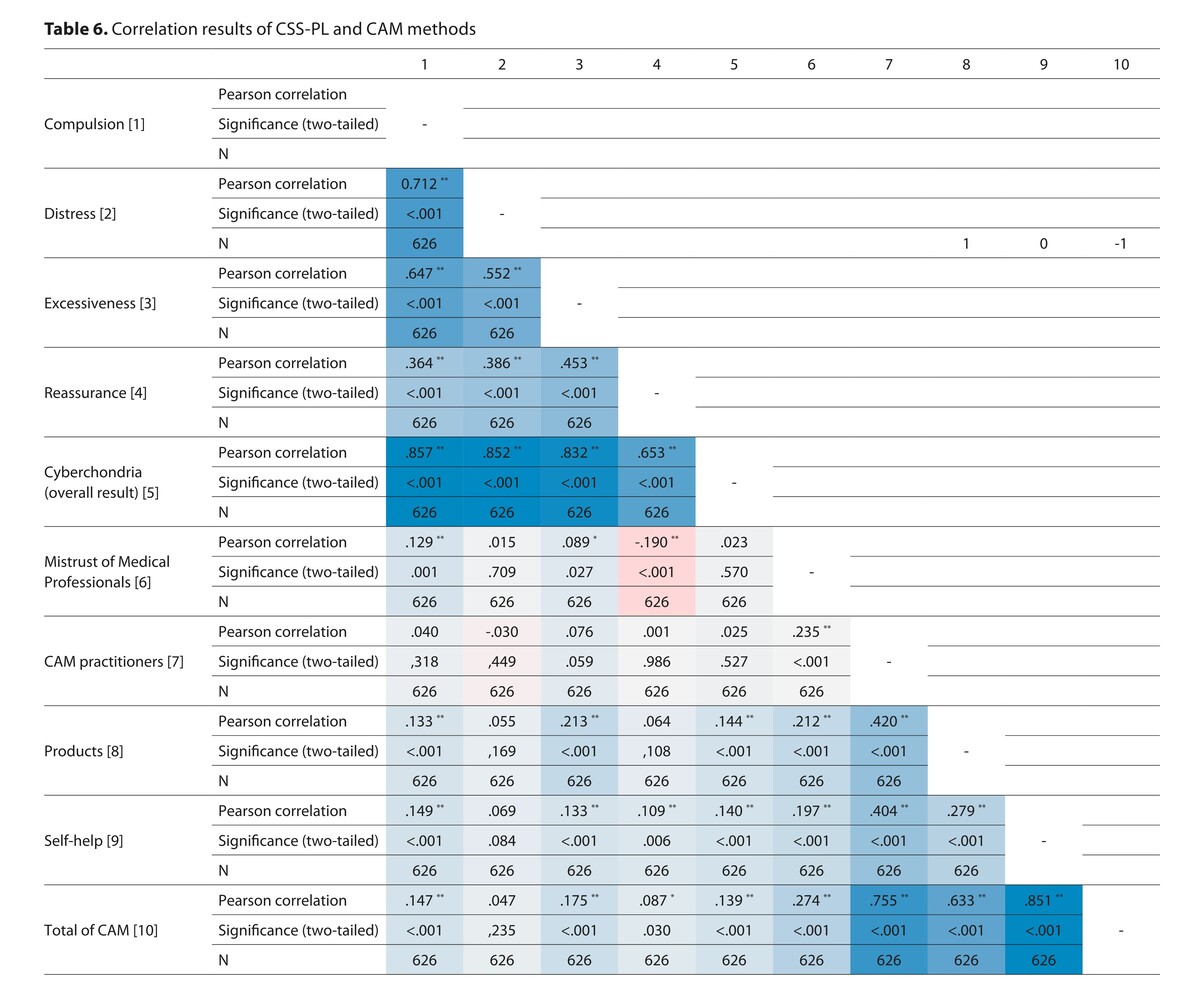

The severity of cyberchondria is associated with ‘a greater number of CAM products used’ (beta = 0.101; p = 0.043), ‘a greater number of self-help techniques used’ (beta = 0.210; p<0.001), searching for knowledge about CAM on the Internet (beta-0.199; p<0.001), using sources other than books (beta = -0.114; p = 0.025), younger age (beta = -0.170; p<0.001) and worse education (beta = -0.101; p = 0.033).

Conclusions:

The research results indicate that there is a link between cyberchondria and the use of CAM. However, since some components of the CSS-PL scale and self-rated health were not associated with more frequent use of CAM, it is likely that these results may not be fully reliable. The association between cyberchondria and CAM use should be investigated in further studies using comprehensive medical interviews.

Cyberchondria has been described relatively recently as a behaviour characterized by excessive Internet searching for medical information related to increasing levels of health anxiety. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) refers to a broad set of health care practices that are not part of a country’s traditional or conventional medicine, and are not fully integrated into the dominant health care system The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationship between cyberchondria and the use of complementary and alternative medicine.

Material and methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted from 25 April – 25 December 2022. A computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) survey technique was used. The study population consisted of 626 respondents who took part in the study.

Results:

The severity of cyberchondria is associated with ‘a greater number of CAM products used’ (beta = 0.101; p = 0.043), ‘a greater number of self-help techniques used’ (beta = 0.210; p<0.001), searching for knowledge about CAM on the Internet (beta-0.199; p<0.001), using sources other than books (beta = -0.114; p = 0.025), younger age (beta = -0.170; p<0.001) and worse education (beta = -0.101; p = 0.033).

Conclusions:

The research results indicate that there is a link between cyberchondria and the use of CAM. However, since some components of the CSS-PL scale and self-rated health were not associated with more frequent use of CAM, it is likely that these results may not be fully reliable. The association between cyberchondria and CAM use should be investigated in further studies using comprehensive medical interviews.

REFERENCES (17)

1.

Bagarić B, Jokić-Begić N. Cyberchondria–Health Anxiety Related to Internet Searching. Socijalna psihijatrija. 2019; 47(1): 28–50.

2.

Starcevic V. Cyberchondria: Challenges of Problematic Online Searches for Health-Related Information. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(3):129–133. doi:10.1159/000465525.

3.

Vismara M, Caricasole V, Starcevic V, et al. Is cyberchondria a new transdiagnostic digital compulsive syndrome? A systematic review of the evidence. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;99:152167. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.15216.

4.

Laato S, Najmul Islam AKM, et al. What Drives Unverified Information Sharing and Cyberchondria during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Eur J Information Sys. 2020;29(23):288–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/096008....

5.

Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-top.... (Accessed on 14 May 2023).

6.

Jędrzejewska AB, Ślusarska BJ, Jurek K, Nowicki GJ. Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the International Questionnaire to Measure the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (I-CAM-Q) for the Polish and Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1):124. doi:10.3390/ijerph20010124.

7.

van der Werf ET, Busch M, Jong MC, Hoenders HJR. Lifestyle changes during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1226. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11264-z.

8.

Moraliyage H, De Silva D, Ranasinghe W, et al. Cancer in Lockdown: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Patients with Cancer. Oncologist. 2021;26(2):e342-e344. doi:10.1002/onco.13604.

9.

Quandt SA, Verhoef MJ, Arcury TA, et al. Development of an international questionnaire to measure use of complementary and alternative medicine (I-CAM-Q). J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(4):331–339. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0521.

10.

Bryden GM, Browne M. Development and evaluation of the R-I-CAM-Q as a brief summative measure of CAM utilisation. Complement Ther Med. 2016;27:82–86. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2016.05.007.

11.

Buchanan EA, Hvizdak EE. Online survey tools: ethical and methodological concerns of human research ethics committees. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2009;4(2):37–48. doi:10.1525/jer.2009.4.2.37.

12.

Whitaker C, Stevelink S, Fear N. The Use of Facebook in Recruiting Participants for Health Research Purposes: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(8):e290. doi:10.2196/jmir.7071.

13.

Bajcar B, Babiak J, et al. Self-Esteem and Cyberchondria: The Mediation Effects of Health Anxiety and Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms in a Community Sample, Curr Psychol. 2021;40, 2820–2831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144....

14.

McElroy E, Shevlin M. The development and initial validation of the cyberchondria severity scale (CSS). J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28(2):259–265. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.12.007.

15.

Markham A, Buchanan E. Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee (Version 2.0). Available online: https://pure.au.dk/ws/files/55... (accessed on 19 March 2023).

16.

Turhan Cakir A. Cyberchondria levels in women with human papilloma virus. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022;48(10):2610–2614. doi:10.1111/jog.15354.

17.

Fionda S, Furnham A. Hypochondriacal attitudes and beliefs, attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine and modern health worries predict patient satisfaction. JRSM Open. 2014;5(11):2054270414551659. doi:10.1177/2054270414551659.

Share

RELATED ARTICLE

We process personal data collected when visiting the website. The function of obtaining information about users and their behavior is carried out by voluntarily entered information in forms and saving cookies in end devices. Data, including cookies, are used to provide services, improve the user experience and to analyze the traffic in accordance with the Privacy policy. Data are also collected and processed by Google Analytics tool (more).

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.

You can change cookies settings in your browser. Restricted use of cookies in the browser configuration may affect some functionalities of the website.